Treaties in 1837, 1851, and 1858 had compelled the Dakota to surrender millions of acres of ancestral land in exchange for annual annuity payments. Those payments arrived later and later, and when they did, politicians and traders—often demanding compensation far beyond the value of goods delivered—were paid first. The Dakota, once able to rely on the region’s abundant wildlife for food and fur trading, now found the territory depleted and themselves dependent on the settlers who now controlled it.

Some Dakota attempted adaptation, cutting their hair, changing their clothes, and embracing certain white customs. Others resisted, resenting the relentless pressure of new settlers. By summer 1862, distrust and hunger had transformed the region into a powder keg. Annuity payments were again delayed in July, and rumors swirled that the Civil War had drained away the gold owed to them, or that the government would pay in worthless paper currency—a meaningless gesture to a people who dealt in barter.

On August 4, a large contingent of armed Dakota descended on the Upper Agency at Yellow Medicine, their people hungry and malnourished. The men demanded food on credit instead of continuing to wait for promised annuities. Eventually, the warehouse door opened and supplies were distributed on credit, a temporary measure that only delayed an inevitable explosion.

Days later, Dakota leader Little Crow spoke for the Lower Agency bands, requesting the same relief. His request was denied. Trader Andrew Myrick, known for his hostility, famously sneered that the Dakota could “eat grass.” Little Crow, long a supporter of peace, lamented his people’s hunger but faced mounting pressure from young warriors who were furious and desperate. Myrick’s insult brought both sides to the brink.

On August 17, four young Dakota, returning from an unsuccessful hunt, stopped at a settler's farm to steal eggs. When confronted, they killed the farmer and his family. These killings detonated a wider conflict. Soon Dakota warriors struck settlements along the Minnesota River, hoping to surprise settlers before they could counterattack. Over the next five weeks, more than 500 white settlers and roughly 150 Dakota were killed.

The decisive clash came September 23 at the Battle of Wood Lake, where U.S. forces defeated the Dakota. Three days later, the Dakota surrendered.

General Henry Sibley immediately convened a five-man military commission at Camp Release to try captured Dakota and mixed-blood combatants for murder and alleged atrocities. The trials were hasty and deeply flawed—most lasted only minutes, with defendants given little or no chance to mount a defense, and many convictions rested on flimsy evidence. By the time proceedings concluded, the commission had heard 393 cases, convicted 323 defendants, and sentenced 303 to death. Critics condemned the process as a miscarriage of justice.

Bishop Henry Whipple, a staunch advocate for Native rights, reviewed the trial records and appealed to President Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln first requested the names of those convicted of raping women and children but was given only two. He then demanded the names of those proven to have murdered civilians. After careful review, he approved thirty-nine executions, sparing many others. One man, Tatemina, received a last-minute reprieve just days before the execution, leaving thirty-eight to hang.

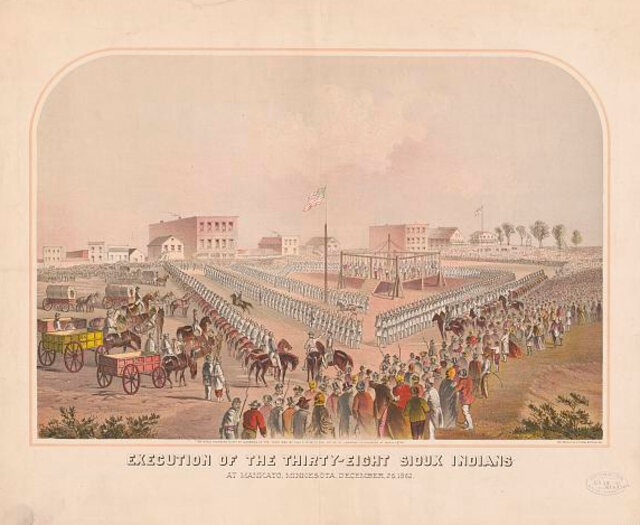

The condemned were brought to Mankato for the mass execution. On the day after Christmas, about 4,000 men, women, and children crowded around a 24-by-24-foot gallows built to hold ten prisoners on each side, while fourteen hundred U.S. soldiers surrounded the square to maintain order.

At the appointed hour, executioner William Duley cut the supporting ropes. Witnesses described the chaos as the men, each with a noose around his neck, plunged through the drop. Before taking their places, many had sung a Dakota hymn together. Newspapers across the country reported the spectacle.

After the war, the Dakota people were forcibly removed from Minnesota. Thousands were exiled to reservations in South Dakota, shattering their traditional way of life. Those executions, together with the conflict itself, ushered in decades of suffering for the Dakota nation—a trauma that would echo through generations.

Minnesota Then

Minnesota Then