She was born Johanna Crow on August 3, 1851, in Chatham, Ontario, Canada, to immigrant parents of Irish or German descent. The family emigrated to the United States when Johanna was nine, settling in Detroit, Michigan. Years later, she married Conrad Steinbrecher, but was widowed in March 1886. She cared for her mother until her passing and soon after relocated to St. Paul.

Crow adopted the name Nina Clifford while in the city. On April 23, 1887, she completed the purchase of two lots "under the hill" on S. Washington Street in the city's Red Light District, directly below the police department and near the Mississippi River.

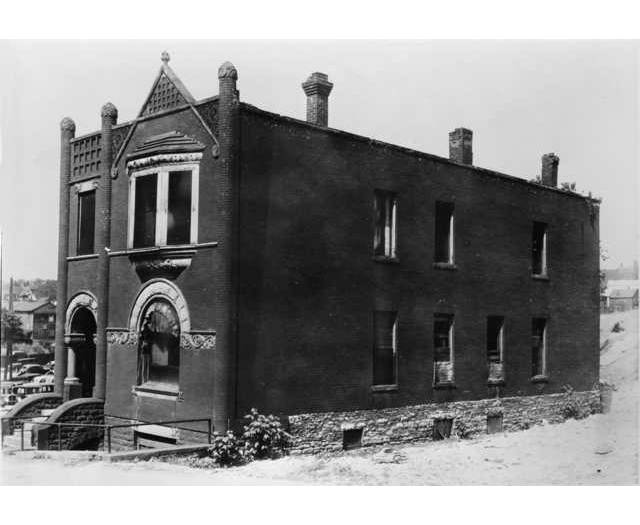

In 1888, she hired architect Walter Ife to design a building on the land. The completed structure became her brothel at 147 S. Washington Street, costing twelve thousand dollars—more than three times that of similar-sized buildings. It stood out dramatically among the residential district's small homes and shacks. Clifford lived next door at 145 S. Washington.

The multi-level, carved brownstone building conveyed an immediate air of respectability other establishments lacked. Patrons who climbed the stairs to the brothel's front door were treated to a high-class experience. Inside, a crystal chandelier hung from one of the many high ceilings. Plush carpeting covered the floors, and music played continuously in the dance hall. Well-dressed servants offered drinks to waiting customers. The brothel featured marble fireplaces, and meals were served on hand-painted porcelain plates. Clifford's business was so popular that she needed to maintain two phone lines.

Despite a quiet acceptance of brothels in St. Paul, a glaring hypocrisy existed. While establishments like Clifford's operated openly, tolerance didn't extend to the women who worked there. These sex workers, referred to as "sports," faced public scorn and belittlement. In stark contrast, Clifford herself flourished, becoming a wealthy businesswoman. She defied the era's belief that women could only acquire wealth through their husbands' deaths. Her brothel's success and her close relationships with the city's elite made her a powerful voice in local affairs.

She had a softer side and a willingness to give generously to those who had less than her. Clifford became known for anonymous donations to local churches and charities. She chartered a car each Christmas and hand-delivered holiday baskets to those less fortunate.

By 1895, Clifford's business was thriving. She operated the largest brothel in the district, employing eleven women as sex workers. At the end of the decade, at least six other addresses on S. Washington Street were operating as brothels. This growth in commercial vice corresponded with a rise in the neighborhood's population density, with an average occupancy of well over six residents per address.

St. Paul's long-running knack of indifference to criminality (for the right price) helped keep Clifford in business. While prostitution was not legal in Minnesota, city officials understood its financial benefits. Local brothel owners came to the police station every month and paid a fine. Most knew it was little more than an unofficial license fee. Authorities had always turned a blind eye to minor social vices like alcohol and prostitution. While the growing Temperance Movement made it more difficult to overlook the problems of alcohol, officials felt prostitution remained a victimless crime.

During a 1913 corruption trial, Clifford testified against the city's former police chief and his co-conspirator. Both men were found guilty. Afterward, she sold a nearby property on S. Washington Street to Minneapolis Madam Ida Dorsey. That consideration, however, probably reflected changing political realities rather than any intention to retire—she continued operating her brothel until her death.

Little was written about Clifford between the trial's close and her death. In the early summer of 1929, she went to Detroit to spend what she believed to be her final days with family. On July 14, Clifford suffered a stroke and passed away. She was buried beside her mother in Detroit's Mt. Elliott Cemetery.

Clifford's brothel—along with much of the district—was demolished in the 1930s. Decades later, in 1997, excavation for the new Science Museum of Minnesota uncovered remnants of her former home and long-shuttered business, offering a glimpse of what life was like in the city's red-light era under the hill.

Minnesota Then

Minnesota Then