At Governor John S. Pillsbury's request, the legislature appropriated $75,000 to rebuild, integrating the standing walls of the former structure into the construction. It was soon determined that the old walls were unsafe and had to come down. A new foundation was laid at the same location that summer. That November, an additional $100,000 to build the new capitol was approved by the legislature.

After a harsh winter in which little work was done, Governor Lucius F. Hubbard discovered that the project to build Minnesota's second state capitol was seriously underfunded. Costs had greatly exceeded the original legislative appropriation of $185,000, and by early 1882 the architect's estimate had risen significantly beyond that amount. Hubbard appealed for additional funds to complete the building in time for the 1883 session. Private citizens of St. Paul donated money without stipulation to help close the funding gap. To reimburse the private donors and complete the building, the legislature approved further appropriations during the 1883 session, bringing the total cost to nearly $360,000.

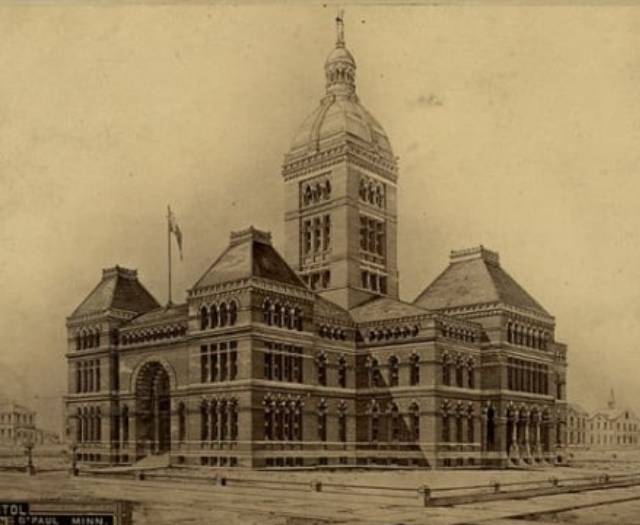

On January 2, 1883, legislators met in the yet-unfinished second capitol, a multi-story red brick structure with sandstone molding. The building was constructed in the shape of a Greek cross, crowned by a central dome that rose nearly two hundred feet into the air. The Senate and House chambers, along with the Supreme Court, were located on the upper floors.

Almost from the moment it opened, the second capitol drew criticism from lawmakers, the press, and the public. Many felt the building appeared hurriedly constructed and lacked the dignity and permanence expected of a state capitol. Its utilitarian design and modest materials contrasted sharply with Minnesota's rapid population growth and expanding economic ambitions. For some observers, the structure seemed less a proud symbol of statehood than a stopgap measure—functional, but clearly temporary.

Fire safety was a key component of the building's construction. Concrete and ash slabs covered the walls and floors, while concrete tiles lined the hallways to prevent fires from spreading. Iron stairways led from the rotunda to the second floor. The boiler was housed in a separate nearby structure, with heat pushed through underground tunnels to radiators throughout the capitol.

Major issues emerged from the outset, none greater than space itself and the way it was ventilated.

Minnesota's rapidly growing state government soon expanded beyond the building's capacity. The lack of suitable space inhibited the political process. There were not enough meeting rooms, and legislators soon began holding official meetings in nearby hotel rooms. Meanwhile, stored documents filled nearly every available nook and cranny. The cramped interior took on an ever-increasing musty odor.

Ventilation issues were exacerbated by a system considered state-of-the-art at the time. Four large air shafts were designed to move air from the basement to the roof, but the mechanism instead contributed to the poor conditions inside. In fact, they were so bad that, years later, the secretary of the state board of health deemed the air unsafe for human beings.

The capitol proved to be one of Buffington's last major works in St. Paul.

By 1893, the building's small size—and its noxious odor—had become too much to overcome. Only a decade after assuming its role as the state's seat of government, serious conversations began about constructing a new capitol—one more reflective of Minnesota's growing confidence and stature. Construction began in 1896 and continued for nine years. The new capitol, Minnesota's third, opened in time for the 1905 legislative session. Legislators and state staff quickly moved their offices up the hill and into what became known as the "People's House."

This did not immediately spell the end for the now-former capitol space. It continued to house state offices for decades, with its last tenant vacating in 1932. The construction of a new State Office Building near the third capitol in the 1930s ultimately sealed its fate.

Minnesota's second capitol, which opened in 1883, was unceremoniously razed in 1938 by the Works Progress Administration. Minnesota's second capitol, which opened in 1883, was unceremoniously razed in 1938 by the Works Progress Administration. Minnesota's second capitol, which opened in 1883, was unceremoniously razed in 1938 by the Works Progress Administration. The land that had hosted both capitols for nearly nine decades was converted to a state-owned parking lot. Development gradually replaced the lot in the years that followed, and the area was designated as part of the Fitzgerald Park neighborhood in 1997 when the district was formally established through the Saint Paul on the Mississippi Development Framework.

Minnesota Then

Minnesota Then